A fun thing to do in extreme cold is to throw hot water into the air. Take a flask and fill it with boiling water to warm it up, pour this away and fill it again. Take the full flask outside, take a cup of this hot water and throw it all up into the air. As the +100�C water meets the cold (in this case -32�C) air, it instantly vapourizes. Most of it is turned into a cloud of steam that drifts gently away and some of the droplets that stay together are instantly turned into small pieces of ice that can be seen streaking down towards the bottom left in this photograph.

It's very weird to throw water into the air but none of it ever actually landing. Also seen in this picture is a solar halo around the sun formed by the ice crystals in the air.

Note - this only happens with very hot water - cold water just lands as cold water.

Mirages are commonly seen on the horizon in the winter or as in this case at the end of winter when the sea-ice has just broken up. They are a result of temperature differences in the bottom few metres just above the ice or sea surface. Air of different temperatures refracts light in different ways, the same phenomena is responsible for "heat haze" as seen above a road on a very hot day. It is the difference in temperature that is important and in this case it is causing a reflection downwards just above the level of the horizon so that objects on the horizon appear to be floating above the sea or ice rather than resting on it.

The Drake Passage is the stretch of water between the most southerly tip of South America and the most northerly tip of the Antarctic peninsula. It is the place where not only are there high and strong winds that blow most of the time, but where the "Circumpolar Current" is squeezed through its narrowest gap. This is a Westerly flowing current that flows around Antarctica powered by Antarctic winds. It flows at the rate of around 140 million cubic metres (tonnes) of water per second, or the equivalent of 5000 Amazon rivers.

The Drakes passage has been described as the roughest stretch of water in the world, it is what must be navigated when rounding Cape Horn and Tierra del Fuego. To reach the Antarctic peninsula it is necessary to traverse this stretch of water at right angles to the current flow. The result is often very lumpy seas indeed as seen in this shot where HMS Endurance is making the crossing.

Mirages are commonly seen on the horizon in the winter or as in this case at the end of winter when the sea-ice has just broken up. They are a result of temperature differences in the bottom few metres just above the ice or sea surface. Air of different temperatures refracts light in different ways, the same phenomena is responsible for "heat haze" as seen above a road on a very hot day. It is the difference in temperature that is important and in this case it is causing a reflection downwards just above the level of the horizon so that objects on the horizon appear to be floating above the sea or ice rather than resting on it.

I once met someone (admittedly a meteorologist) who said that his main reason for going to the Antarctic was because of the amazing skies and clouds that he had seen in pictures. Who can blame him? (if not necessarily agree). The clear (almost) pollution free air and wide open vistas unencumbered by trees, buildings or other clutter give panoramas of the sky that stretch for dizzying distances.

Another of the many optical atmospheric phenomena frequently seen in the Antarctic as a result of the scattering of light by ice particles suspended in the air. Such phenomena are usually encountered in the winter rather than summer when lower temperatures make such occurrences more likely.

Another take on the idea that water turns to vapour when it is considerably warmer than its surroundings. In this picture, water is being exposed at the "tide-cracks" that form around offshore rocks and small islands when the tide rises and falls with continuous sea-ice present. As the ice is not flexible it cracks and as it does, exposes an amount of open water to the air. Antarctic sea water varies between about +2�C and -2�C (the freezing point of sea water) over the course of a year, so in the case of this picture, the exposed sea water is more than 30�C warmer than the surrounding air. The result - it begins to turn to a vapour being so much warmer. The sunshine on this day serves to make it more visible and different temperature layers in the air cause it to rise to a band above the clearer air close to the ice surface.

A F?hn bank is formed by a F?hn wind. This is a warm contour-hugging wind that is blowing across Coronation Island in the South Orkneys group in this case. As the warm (relatively to the ice and rock) wind blows across the land, it causes snow and ice to sublime. That is to turn directly from a solid to a gas without passing through a liquid phase, so causing the cloud layer that can be seen - the same thing may happen when you open the door to your freezer and "smoke" comes out. The overall effect as seen from a distance is that the land is covered by a very large duvet. The gross contours can be seen through the cloud layer, but all of the finer detail is obscured.

Received from an Antarctic met man: The F?hn effect is dominated by "blocking". Wind, approaching a ridge, will either go up and over the ridge (normal) or come to a stop and then flow round the sides. South Georgia often experiences this latter.

Which of the two (up and over or round the sides) depends on the temperature gradient (stability), and wind speed,. If it's stable, the air at the ground is cold and "heavy" and wont flow up and over the top, it goes round the side. BUT, the air at the top of the ridge and just above the ridge, flows over and then down. Air aloft is already warm (because its stable, cold at the bottom), it then descends and gets even warmer and dryer ...a F?hn. South Georgia has these often. If the air is just between the flow round the sides (Froude > 1) of up and over.

At the beginning of the austral winter starting around March, the loose pack ice that has spent the summer months circling Antarctica begins to drift northwards. Pack ice is old sea-ice, frozen sea water that is a year old or more, it froze and formed elsewhere and later floated off with the winds and currents. Pack ice is heavy stuff and when it arrives somewhere it has the effect of steadying the ocean swell. The continuous rolling motion of the sea is stopped completely by a relatively narrow band of pack ice only 100m or so wide. The result is that where pack ice is present in reasonable quantity, the sea calms down sufficiently for low temperatures to freeze it easily - moving water cannot freeze as easily as static water.

This is sea-ice in the very early stages of formation. Sea-ice that forms in situ and is attached to the coast is called "fast-ice", it is stuck fast. In this picture the surface of the sea is beginning to freeze as the temperature is dropping to -20C and below. Pack ice has come near to the shore and so all movement of the sea has been killed completely allowing low temperatures to freeze the sea water. At this stage the ice is around an inch (2.5cm) thick but it has a spongy texture, you could poke a finger or certainly a fist through it relatively easily. The patterned effect comes from the rise and fall of the tides. As the tide rises, so the surface of the sea enlarges slightly and so the ice cracks apart, as the tide falls, so the surface of the sea decreases slightly and so the slabs of ice overlap at the edges.

This is sea-ice in the very early stages of formation. Sea-ice that forms in situ and is attached to the coast is called "fast-ice", it is stuck fast. In this picture the surface of the sea is beginning to freeze as the temperature is dropping to -20C and below. Pack ice has come near to the shore and so all movement of the sea has been killed completely allowing low temperatures to freeze the sea water. At this stage the ice is around an inch (2.5cm) thick but it has a spongy texture, you could poke a finger or certainly a fist through it relatively easily. The patterned effect comes from the rise and fall of the tides. As the tide rises, so the surface of the sea enlarges slightly and so the ice cracks apart, as the tide falls, so the surface of the sea decreases slightly and so the slabs of ice overlap at the edges. Sea ice in the process of forming, the shore of the island in the distance is about 5 miles (8 kilometers) away and the whole of the sea surface in-between is made of forming fast ice. Notice how the slabs of forming ice become larger further out to sea as there are less undulations of the coast to push the slabs together as the tide falls.

Sea ice in the process of forming, the shore of the island in the distance is about 5 miles (8 kilometers) away and the whole of the sea surface in-between is made of forming fast ice. Notice how the slabs of forming ice become larger further out to sea as there are less undulations of the coast to push the slabs together as the tide falls. The ice near to the shore here is known as "pancake-ice". This is formed when slabs of ice that are forming are jostled by the wind and / or movement of the sea. The pancakes of ice bash against each other around the edges and start to curl upwards at the edges. "Pancakes of submerged ice joined with others into great sheets, the rubbery green ice thickened, an ice foot fastened onto the shore, binding the sea with the land. Liquid became solid, solid was buried under crystals."

The ice near to the shore here is known as "pancake-ice". This is formed when slabs of ice that are forming are jostled by the wind and / or movement of the sea. The pancakes of ice bash against each other around the edges and start to curl upwards at the edges. "Pancakes of submerged ice joined with others into great sheets, the rubbery green ice thickened, an ice foot fastened onto the shore, binding the sea with the land. Liquid became solid, solid was buried under crystals." A picture taken of consolidated pack-ice. The ice that you see is mainly pack-ice, last years ice that formed elsewhere, broke up and floated here. As the temperature dropped, then this ice became stuck together by fast-ice, sea-water frozen in situ and attached to the coast that acts as a glue for the loose bits of pack. The ice-bergs that you see have been frozen in position and will remain son until they are freed by the spring break-up of the surrounding sea-ice.

A picture taken of consolidated pack-ice. The ice that you see is mainly pack-ice, last years ice that formed elsewhere, broke up and floated here. As the temperature dropped, then this ice became stuck together by fast-ice, sea-water frozen in situ and attached to the coast that acts as a glue for the loose bits of pack. The ice-bergs that you see have been frozen in position and will remain son until they are freed by the spring break-up of the surrounding sea-ice. Once fast ice (sea-ice frozen in situ and attached to the coast) has become established, the patterns of the earlier pieces disappears. The tide still rises and falls however meaning that the sea surface expands and shrinks slightly as it does so. Tide cracks are a result of this movement (as ice is not known for its elastic properties) they are formed when the ice moves apart, they close again when the tide falls. A tide crack is often many miles long, in this case stretching for around 5 miles (8 kilometers), but never more than about 18", 45cm wide between Signy and Coronation Islands in the South Orkneys group. Tide cracks are valuable resources for wild-life as they provide a region where birds such as snow petrels can fish through for krill and also as a breathing hole for crab eater and Weddell seals.

Once fast ice (sea-ice frozen in situ and attached to the coast) has become established, the patterns of the earlier pieces disappears. The tide still rises and falls however meaning that the sea surface expands and shrinks slightly as it does so. Tide cracks are a result of this movement (as ice is not known for its elastic properties) they are formed when the ice moves apart, they close again when the tide falls. A tide crack is often many miles long, in this case stretching for around 5 miles (8 kilometers), but never more than about 18", 45cm wide between Signy and Coronation Islands in the South Orkneys group. Tide cracks are valuable resources for wild-life as they provide a region where birds such as snow petrels can fish through for krill and also as a breathing hole for crab eater and Weddell seals. This is pack-ice in the summer months around the Antarctic peninsula. The ice looks fairly continuous, but has quite a lot of open water between the pieces and so can be relatively easily pushed aside by an ice-strengthened ship, in this case HMS Endurance. Larger pieces such as this one that are hit by the bow of the ship crack up into smaller pieces.

This is pack-ice in the summer months around the Antarctic peninsula. The ice looks fairly continuous, but has quite a lot of open water between the pieces and so can be relatively easily pushed aside by an ice-strengthened ship, in this case HMS Endurance. Larger pieces such as this one that are hit by the bow of the ship crack up into smaller pieces.Proper Ice breakers have rounded hulls and rounded bows rather than being sharp and pointed. When breaking through very thick ice, the front of the ship rides up over the ice and the weight of the ship breaks through.

Passage is slow though, and heavy on fuel. Most of all, it takes an experienced and well informed ice-pilot to be confident in entering such ice so as not to be locked into the pack should the wind direction change and consolidate the ice.

At the end of the winter, rising oceanic swells and increasing temperatures cause the stable winter sea-ice to break-up and begin to drift away from where it formed. This years fast-ice therefore becomes next years pack-ice with a portion of it melting and disappearing completely. Here a small inflatable zodiac-like craft is (not entirely sensibly) negotiating quite close, but relatively light pack-ice. One person drives the boat, while another sits on the bow pushing the larger pieces of ice out of the way with his feet.

At the end of the winter, rising oceanic swells and increasing temperatures cause the stable winter sea-ice to break-up and begin to drift away from where it formed. This years fast-ice therefore becomes next years pack-ice with a portion of it melting and disappearing completely. Here a small inflatable zodiac-like craft is (not entirely sensibly) negotiating quite close, but relatively light pack-ice. One person drives the boat, while another sits on the bow pushing the larger pieces of ice out of the way with his feet.If the wind gets up and closes the ice, it could well be goodbye to the boat and the people in it too.

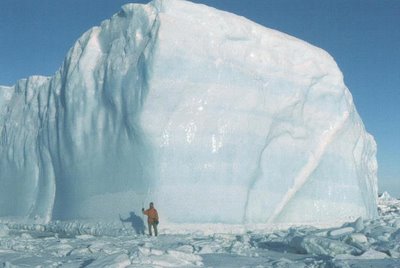

Ice-bergs drift around the Southern Ocean carried by the currents and blown by the winds. In the winter the sea-ice freezes around them and effectively glues them in place until the spring when the ice breaks up and they can begin to move again.

Ice-bergs drift around the Southern Ocean carried by the currents and blown by the winds. In the winter the sea-ice freezes around them and effectively glues them in place until the spring when the ice breaks up and they can begin to move again.During this frozen-in time, it is possible to travel out across the sea-ice and walk right up to the bergs. This guy in the picture has an almost identical picture to this - with me in front of the berg though.

There are lots of different names for different kinds of ice. Large pieces of ice that were once part of an iceberg that broke up are known as "bergy bits" if they are too small to be considered as icebergs themselves. I never did discover when a "bergy bit" was big enough to be a "berg", I think it's a matter of opinion!

There are lots of different names for different kinds of ice. Large pieces of ice that were once part of an iceberg that broke up are known as "bergy bits" if they are too small to be considered as icebergs themselves. I never did discover when a "bergy bit" was big enough to be a "berg", I think it's a matter of opinion!These bergy bits are trapped in the frozen sea-ice in the winter making it possible to walk out to them. In the distance can be seen trapped icebergs and the long low landmass of a nearby island, the two peaks to the left are about 40 miles (64 kilometres) way.

Icebergs are made of freshwater ice and not of frozen sea water. They form from the edge of glaciers when the glacier reaches the sea and either break off in pieces to form an iceberg, or in the case of an ice shelf, begin to float on the sea and then break off from the rest of the glacier as a large slab.

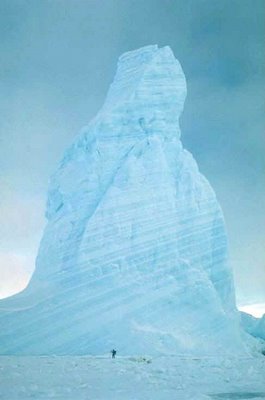

Icebergs are made of freshwater ice and not of frozen sea water. They form from the edge of glaciers when the glacier reaches the sea and either break off in pieces to form an iceberg, or in the case of an ice shelf, begin to float on the sea and then break off from the rest of the glacier as a large slab.Icebergs are made up of snow that has fallen over many hundreds or even thousands of years. The stripes and different coloured layers in icebergs represent different layers of snowfall and the weather conditions under which the snow fell. If it is very cold then a light open layer with much air included will be formed, this gives a paler or white layer. The darker, bluer layers come from snow fall in relatively warm, maybe even wet conditions when little or no air is trapped in the layer.

In addition to this, air is squeezed out of the lower layers of a glacier as more and more snow falls and so the weight of snow builds up.

OK not an iceberg at all, but part of a land-based snow slope. In the spring when the winters snow begins to melt, water flows across the top of glaciers and snow slopes carrying with it dissolved nutrients in the melt water. In these conditions, algae grows within the top layer of the ice or snow catching the goodies as they flow by and taking advantage of the extra energy from the longer days and stronger sunshine.

OK not an iceberg at all, but part of a land-based snow slope. In the spring when the winters snow begins to melt, water flows across the top of glaciers and snow slopes carrying with it dissolved nutrients in the melt water. In these conditions, algae grows within the top layer of the ice or snow catching the goodies as they flow by and taking advantage of the extra energy from the longer days and stronger sunshine.In this case the algae is predominantly a red-coloured species, but further down the slope, green and blue-green colours are discernable. This is relatively short-lived spring phenomena as soon the very snow and ice layer that the algae are living in will melt and the algae will flow down to the sea with the water that provides them with their nourishment. It is not unusual to see distinctly red, green or blue-green topped ice bergs in the spring as a result of the growth of such algae.

There are over 300 species of such algae that live in such harsh and cold conditions. The red colour is a protective chemical (carotenoids such as astaxanthin) that the alga produces against exceptionally high concentrations of visible and ultra violet light that bounces off the snow and ice surfaces and so saturates them to a point where it become harmful and destructive. Such algae are also found in other parts of the world, often in high mountains where extra u-v light due to the thinner atmosphere and again increased light scattering by ice and snow requires protection by similar pigments.

Sometimes, walking across such an area will leave behind red footprints as the algae are concentrated by the walker as the snow is crushed, and sometimes there will be a a faint smell of fresh watermelon accompanying the phenomena.

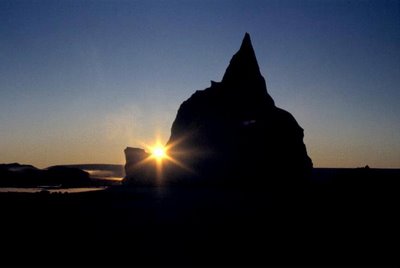

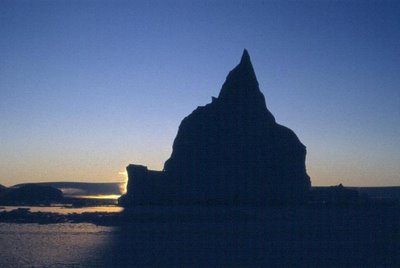

Ice bergs are carved and shaped by wind and wave. As they are eroded, so the balance changes and they tip up to a new stable position. This continuous erosion, moving around and occasional breaking up into smaller pieces produces all kinds of weird and wonderful shapes that belies their original origin as a part of a flat freshwater glacier.

Ice bergs are carved and shaped by wind and wave. As they are eroded, so the balance changes and they tip up to a new stable position. This continuous erosion, moving around and occasional breaking up into smaller pieces produces all kinds of weird and wonderful shapes that belies their original origin as a part of a flat freshwater glacier. Ice bergs are eroded by a combination of temperatures above freezing and the effects of wave action. Here in a fairly rough sea, waves are washing up the side of this berg to a point about 2 metres above sea level and will probably make two separate upright areas that are divided by the developing trough. We did for a short time consider trying to speed through the gap when it was awash in our small powerfully driven zodiac boat, but decided against it - probably for the best!

Ice bergs are eroded by a combination of temperatures above freezing and the effects of wave action. Here in a fairly rough sea, waves are washing up the side of this berg to a point about 2 metres above sea level and will probably make two separate upright areas that are divided by the developing trough. We did for a short time consider trying to speed through the gap when it was awash in our small powerfully driven zodiac boat, but decided against it - probably for the best! The hard angular shapes and edges of this berg remind me of a cubist painting. Notice that the area at sea-level towards the left is very smooth and curved by contrast to the rest of the ice. The sharp geometric edges will probably have been made when this piece of ice calved from its glacier, the fracture planes of the ice being usually straight and plate-like. That it is not yet smoothed out indicates that this region has not yet been under the water to be sculptured into the more usual curves seen on ice bergs, it also means that it only recently fell off the glacier, although it could well be a fracture plane from the collapse of a larger ice berg that broke into pieces.

The hard angular shapes and edges of this berg remind me of a cubist painting. Notice that the area at sea-level towards the left is very smooth and curved by contrast to the rest of the ice. The sharp geometric edges will probably have been made when this piece of ice calved from its glacier, the fracture planes of the ice being usually straight and plate-like. That it is not yet smoothed out indicates that this region has not yet been under the water to be sculptured into the more usual curves seen on ice bergs, it also means that it only recently fell off the glacier, although it could well be a fracture plane from the collapse of a larger ice berg that broke into pieces. It can be quite an unreal experience getting close up to ice bergs in small boats but a really awesome if potentially dangerous thing to do. The effect of light on and through the ice produces a world of blues and white, the berg can usually be seen for several metres below the water surface and there may be icicles hanging down as here where the ice has melted in the sun and water run across the face of the berg before freezing again. If you ever end up in this situation, make sure you have some really good sunglasses and a high factor sun screen for exposed flesh (including that little bit underneath your nose!) as the reflections and brightness especially when the sun comes out can be painfully dazzling with no-where to look that isn't brilliantly lit.

It can be quite an unreal experience getting close up to ice bergs in small boats but a really awesome if potentially dangerous thing to do. The effect of light on and through the ice produces a world of blues and white, the berg can usually be seen for several metres below the water surface and there may be icicles hanging down as here where the ice has melted in the sun and water run across the face of the berg before freezing again. If you ever end up in this situation, make sure you have some really good sunglasses and a high factor sun screen for exposed flesh (including that little bit underneath your nose!) as the reflections and brightness especially when the sun comes out can be painfully dazzling with no-where to look that isn't brilliantly lit.Large irregularly shaped bergs tend to be the most interesting to visit, but also the most dangerous and most unstable. They will break up at some point and they will tilt and move around a lot before settling to a new stable position. If you're in the vicinity when this happens, you may get some big pieces of ice dropped on you or at the very least there will be some major waves and disturbances of the sea. Having said that I've never heard of anyone actually being hurt in such an event - a combination of the rarity of it happening, alertness and speed of the boatman/boat and people just not going near big bergs very often in small boats.

No comments:

Post a Comment